A 26-year-old man has discovered he’s among the 3% with a rare brain condition called aphantasia, causing ‘blindness in the mind.’

Recently, a 26-year-old man discovered he has a rare brain condition called aphantasia.

This condition affects about 3% of the global population.

This unusual phenomenon means he cannot visualize images in his mind, a condition often described as being “blind in the mind.”

Aphantasia has been a topic of interest in psychological studies for several years, though many people remain unaware of its existence.

26-year-old man is among 3% with rare brain condition causing ‘blindness in the mind’

The man, named Joe Yates, realized something was different about him when he struggled to imagine common scenarios that others described vividly.

For example, while friends could easily picture a flock of sheep jumping over a fence, he could only see darkness when he closed his eyes.

The discovery of this condition came as a surprise.

He had always believed that “counting sheep” was just a figure of speech.

Joe Yates didn’t realize that others could actually visualize the sheep in their minds.

His friends often talked about their ability to create mental images, and he found himself feeling left out and confused.

For the man, the implications of aphantasia extend beyond simply lacking visual imagination.

He has realized how this condition affects his daily life and interactions.

For instance, he has often listened to discussions about movie adaptations of books, where viewers express strong opinions about casting choices.

He could not understand their passion until he recognized that most people can visualize characters and settings, which he cannot do.

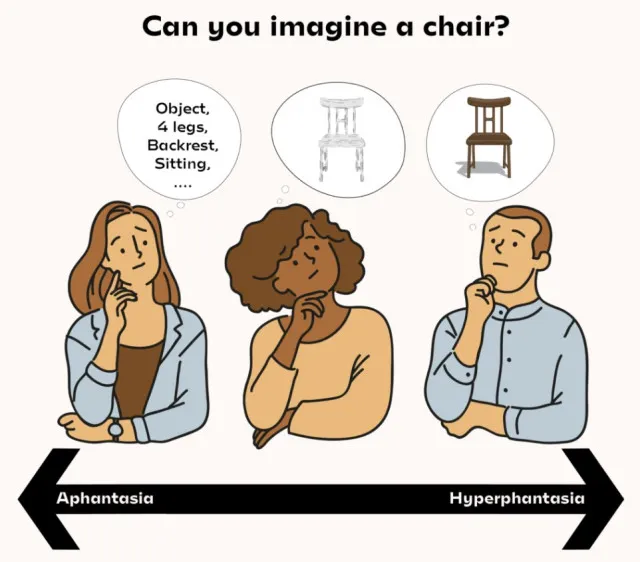

The difference between people who suffer from hyperphantasia and those with aphantasia

Mental imagery exists on a spectrum.

Some people with aphantasia cannot visualize anything, while others with hyperphantasia can create vivid and detailed images in their minds.

Between these extremes are individuals who can see dim or moderately clear images.

The experience of mental imagery varies widely, which makes aphantasia a fascinating subject for researchers.

To determine if one has aphantasia, a simple test involves closing one’s eyes and trying to visualize a common object, like a ball on a table.

Those with aphantasia will struggle to form a clear image, while others can easily picture the details.

This test reveals the differences in mental imagery capabilities among individuals.

While some might view aphantasia as a limitation, many people with the condition report that they adapt well to their circumstances,

They may not feel overwhelmed by intrusive images and can focus more on thoughts and concepts rather than visual distractions.

As a result, they often lead fulfilling lives without significant challenges related to their condition.

Aphantasia was first known in the late 19th century

Aphantasia was first identified in the late 19th century by Francis Galton, who conducted studies on mental imagery.

However, it wasn’t until a study published in 2015 by Professor Adam Zeman from the University of Exeter that the term “aphantasia” was coined.

The name comes from the Greek word “phantasia,” meaning imagination, with the prefix “a-” indicating absence.

Professor Zeman describes aphantasia not as a disorder but as an intriguing variation of human cognition.

“I try to avoid calling it a condition, as I don’t think it is pathological, and tend to speak of ‘an intriguing variation in human nature’.” he said.

He notes that individuals with aphantasia might have subtle differences in brain connections.

These differences can affect how thoughts are translated into images.

This variation may have a genetic component, although some cases can develop after brain injuries or psychological issues.

“Rarely, aphantasia can be acquired as a result of brain injury or psychological upset – depression, depersonalisation especially,” Zeman added.

“In terms of treatment – it’s probably not needed. People with aphantasia get along just fine and there may be advantages to not being bombarded with images…

which is lucky as there is currently no reliable way of ‘curing’ aphantasia.”